At first light, we arrived and parked at the south end of the ridge marking Dave's Deer Mine. Deer were flooding out of the alfalfa field and up the steep, rocky ridge. Even if there had been a buck among them, it was a little early to shoot. More importantly, I wanted AJ to hunt a deer and not merely shoot one.

We climbed the ridge, moving carefully and not trying to overly spook the bunches of deer that seemed to be all around us. It was a very foggy morning, and only in fits and spurts could we see more than a hundred yards or so. Though we did get a good look at a dozen or more deer, we could not put horns on any of them, and so continued along the ridge toward the saddle. At the saddle, the fog began to lift a bit.

We spotted a small herd of deer on the ridge across from us, and one was a good buck. It was much too far to shoot; after the first day's deer hunting disappointment, I was determined to keep the range well under 200 yards. Unfortunately, as the fog lifted the wind shifted and when they scented us the deer vanished into the rocks and trees at a crest in the ridge.

And so we continued working our way along the ridge's spine, swerving left and right to glass the rocks and sage and mountain mahogany on either side. Though we saw several bunches of deer, there seemed to be no bucks among them. It was the tail end of the rut, the large herds had broken up, and I feared the bucks might have left for another area.

But then we saw a few mulies feeding far below us, and as we glassed the grassy cleft between two finger ridges we saw more and more deer--mostly bedded. At 500 or 600 yards, it is difficult to see a small-antlered buck through our lightweight binoculars. When two deer began butting heads however, I knew they were bucks even before we caught a few flashes of sunlight from their antlers. This was a perfect setup for a stalk: we could back down the ridge, stay out of sight, and peek over from a prominent outcrop only a hundred yards or so from the deer.

We nearly reached that prominent outcrop when the volley of shots began from across the river. The shots were clearly being aimed toward us, though at a much lower point at the base of the ridge. We could see the four hunters, at least two of them with their rifles rested on the hood of the truck. At first I thought they might be shooting at "our" deer, but then I could see that the furthest finger ridge would block their view into the grassy cleft.

But the racket did spook our deer, and we could see the first of them beginning to move up the cleft between the finger ridges--directly at the spot where we had been sitting when we first saw them. No matter. We hurried over to the edge of the ridge, found a waist-high rock, and I unslung my knapsack as a rest for AJ to shoot from. The deer were now in a perfect single file, moving slowly but purposely along.

Toward the rear, a big forkhorn paused to look back. AJ had already spotted him. The rifel roared, the little buck flopped down, and the rest of the herd continued up and over the ridge.

Death seldom comes easily, and we watched as the deer struggled, kicked, and tried to raise his head. He was largely obscured by rock and sagebrush, and I advised AJ to shoot again only if he had a clear shot. This proved unnecessary, and within a long minute or so the buck became still and never moved again.

We approached cautiously, partly because of the steep slope and partly because I have several times seen "dead" deer jump up and run. We admired the deer, thanked the deer and the mountain, and then the work began.

We approached cautiously, partly because of the steep slope and partly because I have several times seen "dead" deer jump up and run. We admired the deer, thanked the deer and the mountain, and then the work began.It was a fine shot, a hunter's shot. The bullet had angled in from high behind a shoulder and exited through the liver and one lung.

As always, it was a rough drag down the mountain side, through the sagebrush and over the rocks. We dropped into the coulee that drained the cleft, and though there was not much of a trail there was some snow and that helped ease the drag. As we neared the railroad tracks, I sent AJ back to the truck for the bike and I sat down to enjoy the sun, the sight of an osprey fishing the river, and my lunch.

I also watched the idiots who had shot from across the river walk up the railroad tracks cans of beeer in hand.

they found the one deer they had killed with their 7 or 8 shots, field dressed it, and begin dragging it out over the rough ballast between the tracks.

AJ arrived--much more quickly than I expected. It would have taken me a half hour or longer to reach the truck, and at least that long to return (including a pause for lunch!). We loaded the buck on the bike, setting his pelvic opening over the saddle, tying one leg to a handle bar, and the other leg and neck to the other handle bar. [I thank Rick and Sam Douglass for demonstrating this method to me many years ago, when Sam was about AJ's age.]

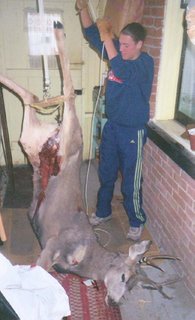

AJ skinned the buck that afternoon, and butchered it the next. After only one previous lesson (on his elk), he did a good job with little help. Quick study, this boy.

And now I need to find an elk for my own freezer. I hunted a certain big elk bull for the 3rd time Saturday, and for the 3rd time he outwitted me. So much for "three time's a charm." From here on, I'll be very happy to take an elk cow, thank you very much to the hunting gods.